Monday,25,2018

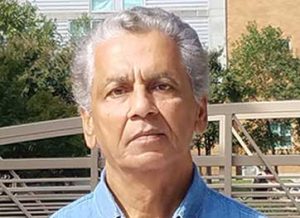

An interview with Prof. Imtiaz Habib

An interview with Prof. Imtiaz Habib

(Old Dominion University)

Year of passing B.A. and M.A.

1973, 1976

Details of institutions concerned.

- Oxford University (New College).[Earlier, I spent three years in the B.A. (Hons.) English program at Dhaka University, but had to leave the country in 1971 due to the Pakistan Army’s genocide campaign].

- Graduate work, of the Ph.D. level, was at Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana, U.S. 1978-84.

When did your first encounter with Shakespeare take place (at school or college)?

Probably at school.

College and university syllabi (Shakespeare plays and poems).

Hamlet, Macbeth, Julius Caesar, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, The Merchant of Venice, Richard II, 1 Henry IV.

Who taught the texts in question?

Professors Jyotirmoy Guhathakurtha, K. S. Murshid, and Razia Khan Amin.

What techniques were used (e.g., close reading, lecture demonstration, group discussion, seminars etc) for teaching Shakespeare?

Lectures, close readings.

What traits of any particular teacher impressed you most?

Penetrating historical and cultural generalizations, and text analyses.

Did the teachers maintain total gravity in class or cut jokes to enliven the reading experience?

A judicious mixture of both.

Did the teacher enact the scenes in the class room?

No, certainly can’t remember any.

Was the teacher very particular about pronunciation and accent?

Not consciously, I think, but it certainly came across as polished and charismatic.

Did the teacher discuss philology and prosody while reading Shakespeare?

Yes, somewhat.

Did the teacher refer to literature in other languages while discussing Shakespeare? For example, would the teacher mention Dante, Kalidasa or Tagore while reading Shakespeare with the students?

Yes, somewhat, Tagore, Goethe, Byron, were some authors I remember being invoked.

Were expletives and sexual references omitted?

Yes. By today’s standards, these were quite gentlemanly and lady-like classes, and nor did we at that time (late sixties in Dhaka, and early seventies in Britain) expect them not be.

How far was the socio-historical context of plays discussed?

Marginally, these were essentially, innovative new critical readings that we were exposed to. Note that for this (and the previous four or five questions), I am talking about my undergraduate college experience. The graduate experience at Indiana University was profoundly different in the multifarious cultural-political-historical and critical-theoretical grounding in Shakespeare I acquired there. It was there that I received my scholarly awakening and professional training.

Were Shakespeare’s contemporary dramatists given the same amount of importance in the classroom?

Yes, to the extent that there were separate courses for them in the undergraduate curriculum. Sadly, due to curricular over-crowding among other reasons this practice has died out in the undergraduate curriculum in many colleges and universities in the West

Were students encouraged to think independently and challenge the teacher?

Yes, at Oxford, in the tutorial sessions.

What were the editions and critical material prescribed and used?

I don’t remember the editions prescribed at Dhaka University, but at Oxford there were no prescriptions of texts or critical readings. We were just encouraged read as widely and deeply as possible—to simply “jump in at the deep end” as one of my tutors albeit in Middle English literature (Christopher Tolkien, the son of J.R.R. Tolkien) once cruelly put it!

Could you describe the examination and question pattern?

At both Dhaka and Oxford examinations were in a block at the end of three years, in the form of one out of eight exams devoted to the English Renaissance, and the questions were topical and thematic essay questions that required quite hard, perspectival thinking on the subject.

This was of course in addition to the two Tutorial sessions each semester with one professor each week, in which the professors concerned were not necessarily the ones who lectured on Shakespeare.

At Oxford, there were no regular mandatory lecture classes, only two one-on-one hour long tutorials each week each term with professors specializing in an area of the syllabus, in which extended discussions were followed by challenging essay writing assignments

At Oxford, there were no regular mandatory lecture classes, only two one-on-one hour long tutorials each week each term with professors specializing in an area of the syllabus, in which extended discussions were followed by challenging essay writing assignments. Shakespeare studies occurred in one of these sessions in one semester. There were public lectures by visiting scholars, in which attendance was encouraged but not mandatory

Did the teacher refer to stage and film productions of Shakespeare?

As far as I can remember, not much.

Were the texts related to performance conventions?

Marginally at Dhaka, bit more at Oxford.

Were there any performance of Shakespeare at the institution?

Yes, many, at Oxford. At Dhaka there were occasional productions in English, put on by the British Council and performed by visiting British acting troupes. There were also occasional productions in Bengali based on translations by Dhaka University faculty, some of which were quite striking and memorable in their originality and which are now regarded as landmarks in the cultural history of Dhaka in the twentieth century, e.g. MUKHORA ROMONI-R BOSHIKORON (The Taming of the Shrew) by Professor Munier Choudhury of the Bengali department).

Could you provide an account of classmates who later distinguished themselves as teachers, performers etc?

The only one I can think of is Alauddin Zaheen, who was a brilliant theatrical impresario whose deep grounding and profound understanding of classical performance and production techniques was so seminal that it was, in my opinion the impetus for the vibrant Dhaka professional theatre industry that emerged in the city after Bangladesh’s independence in 1971. I have no doubt whatsoever that it was the impact of Zaheen’s towering theatrical expertise that was responsible for the development of his younger sister, Sara Zaker, as one of the star performers in Dhaka’s theater industry, a standing she still has even if she may have now retired. I have yet to see the brilliant theater genius and thinker that Zaheen was acknowledged as such even today. Zaheen was a class mate and close friend in my college years in Dhaka. He was killed in Bangladesh’s independence war in 1971.

What are the noticeable changes in Shakespeare pedagogy and student reaction over the decades?

Richly informed and keenly interrogative cultural studies, especially of the feminist, Marxist, cultural materialist, and post-colonial varieties—in India and the West—have made Shakespeare studies far more challenging.

With the advent of post-structuralism in its varied forms from the seventies onwards, the study of Shakespeare has of course become much more historically grounded and theoretically informed than it was when I was a student. Richly informed and keenly interrogative cultural studies, especially of the feminist, Marxist, cultural materialist, and post-colonial varieties—in India and the West—have made Shakespeare studies far more challenging.

What differences have you noticed between Shakespeare teaching in your country and abroad?

[I take it that “my country” refers to my country of origin—Bangladesh, and Bengal generally speaking—and not the U.S. where I have been residing for nearly three decades.]

The main differences—from when I was living there, and now (as garnered from a recent visit)—are mainly a complete lack of historical grounding, and what I would call an illiteracy more or less about critical theory, especially in the ability to use it for effective interventionist analyses of material and social texts.

Do you think that Shakespeare is an overrated author?

I would say, yes and no. The history of Shakespearean “Bardolatory” extending from the eighteenth to the twentieth centuries, that relentlessly produced Shakespeare as a cultural icon of a male, white Eurocentric imperial-colonial-patriarchal modernism makes common “ratings” of Shakespearean “greatness” almost meaningless. At the same time, a sober consideration of Shakespeare as a particular writer in a particular time and place would certainly oblige a view of him as a serious literary figure in whom strengths and deficiencies coexist contradictorily as much as they do in all poet and playwrights. Instead of approaching him in terms of an individual time-transcending genius (or any such nonsense), it is far more productive to study him in terms of the political, cultural, and historical forces that produced him at the time and in the place that they did.

How would you react to the present trend of de-glamourizing and de-canonizing Shakespeare?

With approval. Such moves are healthy necessary steps towards serious studies of him.

How would you react to the phenomenon of reading Shakespeare in a simplified language or in paraphrase, now popular among students in the West?

As an exclusive practice this is worthless. But as the beginning of a graduated immersion into the complete historical world of the Shakespeare topic it could be helpful.